“Did you come here alone?” My obstetrician asked as I lay on the exam table. My 8-month-pregnant belly was exposed and lathered with an anti-static gel that was cold, thick, and sticky. I nodded yes, and felt the deepest alone I’d ever felt. I couldn’t talk through my sobs, swirling thoughts, nausea, dizziness, and mostly my desire to change time. If I could just go back. If I could just pretend it was a dream. If I could just ignore her and be blissfully ignorant.

I managed to audibly say my husband, Mark’s name and through an ache unlike anything I’ve ever felt said, “Emergency contact.” He didn’t answer his phone. I shook so hard that I couldn’t hold my phone. The nurse found his number and dialed for me. As soon as he picked up, I wailed,

“She doesn’t have a heartbeat.”

The wait for Mark to arrive at the doctor’s office was only 15 minutes, but it felt like hours. Time is relative and any point of reference stopped. Everything stopped. But my mind raced. He needed to bring our 2-year-old daughter, Juliet, with him. We were in the peak of the COVID pandemic with no family nearby and no childcare. I thought of Juliet. I begged to just change time. I pleaded to not have to hear, “I’m so sorry, your baby passed.”

As I waited for him, I called my lifelong friend and cried with her. I texted my other friends the news. I texted my new boss of 4 weeks – I had just started a job. How do I tell him or our team of 80 people that I never met in person? I had just penned an article on LinkedIn about getting a job in my third trimester. Did I jinx myself? I felt embarrassed. I texted my doula, the only person I knew that could tell me what to do. I removed myself from a Facebook chat with five of my friends whom I was going to be on maternity leave with. I was panicking and desperately trying to erase it all. I started to “handle” the situation but my mind and actions were completely uncontrolled.

When Mark and Juliet arrived, my OB went through a list of next steps, but I only heard a slew of random words: Sepsis. Delivery. Stillbirth. Time. Contractions. Today. My eyes were sore; I ran out of tears. I closed them and prayed and bargained and pleaded for this to not be real.

I delivered Lucy April 21, 2020 at 30-weeks. She was still, time was still, and so was I. A stillborn delivery is the same as a live birth. The contractions, epidural, pitocin, and pushing. But there is no small cry. No joy. The room was dark and quiet; my heart was too. I was not strong enough and I didn’t want to be.

The nurse brought Lucy to Mark and me. She was so small and bundled in a blanket and perfectly placed hat. I held her and cried, and the only words I could say were, “I’m so sorry.” I felt as though I had an obligation to keep her safe and warm and nurture her in my womb. To ensure she grew stronger and reached the milestones for a healthy baby. I failed and I felt so gut-wrenchingly guilty for failing her.

We left the hospital the next day. I was in a wheelchair holding a lavender purple box of Lucy’s photos, tiny footprints, hat, and blanket. The box sat on my lap on top of a stack of discharge papers, funeral and crematory providers, postpartum depression pamphlets, and stillbirth support group information. I couldn’t help but to choke back tears and think I cannot believe I’m leaving with a box instead of our baby. I closed my eyes. They stung from exhaustion and salty residue. A reminder of the tears that would periodically flood my eyes. I can’t believe this is actually happening. I can’t believe this actually happened. It still feels like an alternate life… did this really happen?

The next few days were dark. We tried to handle our affairs but everything continued to be an uphill battle. Nothing was simple. Finding a funeral home was nearly impossible. There was a 3-week delay in cremation due to the increase in deaths as a result of Covid. Requesting bereavement required a birth and death certificate, stillbirths don’t receive birth certificates and death certificates were also backlogged. Testing to find out what happened was also backlogged.

I visibly looked pregnant so, leaving the house was filled with “Congratulations!”… “When are you due?” conversations with strangers. Those resulted in me consoling them for feeling badly when I explained what happened. A year and half later, I still have these conversations. The dentist, hairdresser, barista, neighbor, the woman I met once at a volunteer event, the well-meaning colleague who asks if Juliet is my only child or how many children I have. How do you tell people your baby died? I have practiced my answers. I now use standard responses that vary by situation.

After a couple months, we found out that Lucy died from congenital cytelomeglovirus (CMV), a virus that most people have had before 40. It is only dangerous if you contract it for the first time while pregnant. I dodged a global pandemic but succumbed to a common virus I didn’t even know I caught. I dove into understanding everything I could about CMV. It’s more common in pregnancy than Down Syndrome, toxoplasmosis (the cat urine thing), spina bifida, and fetal alcohol syndrome. The guilt still loomed over me – could I have prevented this? Why couldn’t I keep Lucy safe.

I sought help from a psychiatrist and psychologist. I felt out of control as if I was unable to touch the ground. I would scream into my pillow or in my car. I would wake up feeling pregnant. My breasts would ache, full with milk for a baby I could not nurse. Biology can be infuriating. Mentally I was breaking. It was summer but I felt as though I was stuck in fall. I bought $500 worth of sweaters and pants while it was 90 degrees outside. Maybe money could help me change time? Fall was when I became pregnant with Lucy, before everything fell to pieces. My psychologist gave me some signs to look out for, concerned this trauma could trigger a dissociative identity disorder.

Lucy’s death and birth changed me. I fortunately evaded severe depression and dissociative identity disorder. I have grown to be more kind, mindful of language and assumptions, and forgiving of myself and others. I know now that it’s possible to feel a spectrum of emotions at once, and really feel them – joy and total despair, sad and happiness, anger and serenity. My priorities have shifted to my family and my patience only holds muster to meaningful conversations. My soul is too tired for small talk or the weather. Going through this experience has made me more vulnerable and willing to unapologetically show that to anyone.

I’ve also grown to know a sadness that will always be with me. It’s an innocence and blissful ignorance that is gone forever. Not every pregnancy results in a baby. And, there isn’t always a silver lining. Sometimes things just suck and there isn’t a happy ever after. Not everything happens for a reason. And that’s ok too.

My capacity for love and hope however has increased. I find happiness in people’s stories in a way I didn’t before. I pause to enjoy Juliet yelling “Mom” as she runs up the driveway from preschool with her new artwork in hand. I love my husband more deeply and fully than I otherwise could have.

I think of Lucy every single day. She broke me and healed me at once. Her life and death, though brief in time, has not only given me lifelong aching but, hope too. Will this change in time? Maybe. But, time and I have an unreliable relationship.

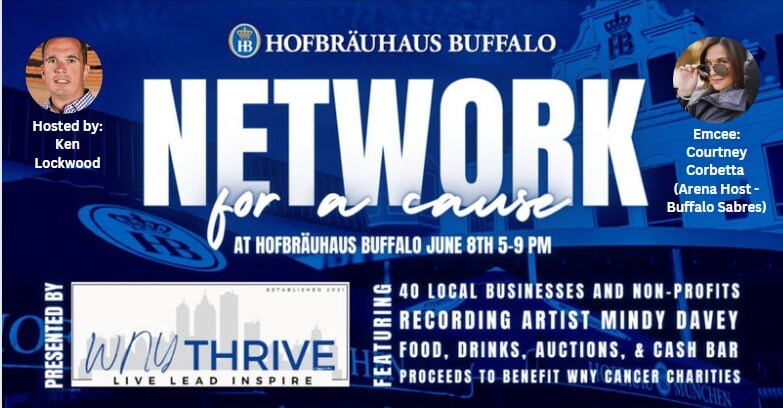

Jennifer Loga, a native of Buffalo, NY, lives in Maplewood, NJ with her husband Mark, daughters Juliet (3), Abigail (1 month) and dog, Pickles. Following Lucy’s death in 2020, Jen and Mark have raised more than $50,000 for stillbirth, pregnancy, and CMV causes. To learn more about CMV, click here. To support or volunteer for better pregnancy outcomes, click here.